A decade after losing his leg, Scott Bryson had nearly given up on walking again. Crutches were painful, prosthetics unbearable—and hope was wearing thin.

Then came a revolutionary procedure at UT Southwestern.

The 50-year-old father of three from Collinsville, Texas, is now back on his feet thanks to osseointegration—a surgical technique that embeds a titanium implant directly into the bone of an amputated limb, allowing for a more secure and natural connection to a prosthetic.

“This is a new lease on life for me and my family,” Bryson said in a news release.

“I told my youngest daughter that when she gets married someday, I’ll be able to walk her down the aisle.”

From dental implants to limb restoration

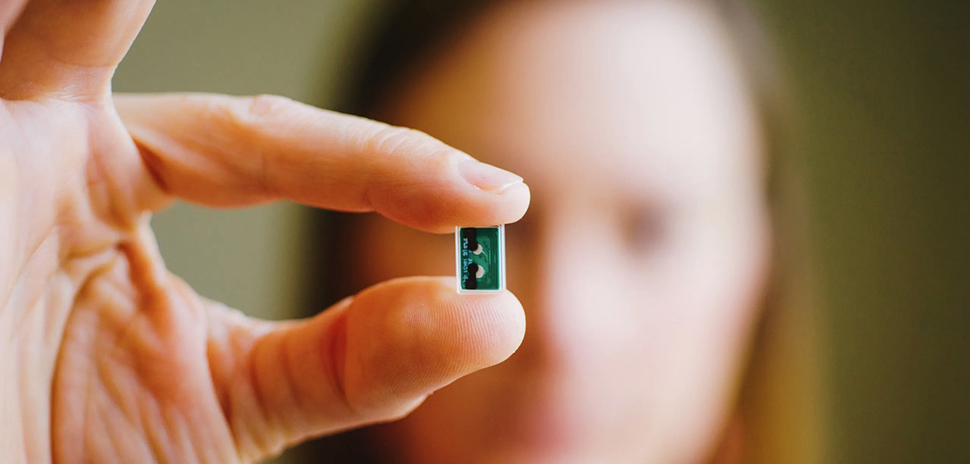

Osseointegration, also called bone-anchored prosthesis surgery, takes its inspiration from an unlikely place: the mouth. The technology is a spinoff of dental implants, which have been in use since the mid-1960s. Just as titanium posts fuse with the jawbone to support prosthetic teeth, osseointegration uses treated titanium to bond with a patient’s leg or arm bone—forming a stable base that connects through the skin to a prosthetic limb.

“The implant becomes part of the body, allowing for more natural attachment and control,” said Dr. Jonathan Cheng, professor of plastic surgery at UT Southwestern, said in a statement earlier this year. The first U.S. implants for prosthetics were approved by the FDA in 2020.

Dr. Cheng and Dr. Alexandra Callan, associate professor of orthopedic surgery and a Dedman Family Scholar in Clinical Care at UTSW, lead the multidisciplinary osseointegration program—one of only two in Texas and the only one in North Texas.

A team approach to restoring mobility

UT Southwestern’s osseointegration program draws on expertise from across the medical center, including orthopedic surgery, plastic surgery, prosthetics and orthotics, physical therapy, pain management, and biomedical engineering.

UT Southwestern said the procedure requires extensive multidisciplinary expertise, which is why only a few hospitals nationwide offer it.

Over several years, Dr. Callan and Dr. Cheng have built a team knowledgeable in osseointegration care—drawing on specialists from rehabilitation, prosthetics and orthotics, biomedical engineering, and pain management.

The surgery is done in two stages. In the first, surgeons contour the patient’s residual limb and implant a titanium cylinder into the bone’s medullary canal. Over the following months, the bone gradually fuses with the implant. Once integrated, a second surgery connects an abutment that protrudes through the skin and anchors the prosthetic.

So far, UT Southwestern has performed the first stage of osseointegration on 10 patients and the second stage on four. All have involved lower extremities, but the team has begun evaluating candidates with upper limb amputations as well.

A better prosthetic experience

The benefits are substantial. Osseointegrated prostheses are easier to put on, more comfortable to wear, and better tolerated by patients with short stumps who struggle with socket-fit issues. Because the prosthetic is anchored directly to bone, movement feels more natural—and many patients regain sensation through the limb, improving balance and safety.

Movement with an osseointegrated prosthesis is more physiologically normal than with traditional socket-based options, leading to a more natural pattern of wear on joints and surrounding structures like the hips and spine, Callan explains.

For Bryson, the decision came after years of pain. A car accident after high school graduation shattered his leg. After 30 failed surgeries, he underwent an above-the-knee amputation in 2015. But nerve pain and neuromas made wearing a traditional socket prosthetic excruciating.

He used crutches for nearly a decade, which damaged his shoulders and made day-to-day life increasingly difficult.

After undergoing stage one of osseointegration surgery in June 2023 and the second in November, he began rehab at UT Southwestern in January 2024. Working with physical therapist Michael Marmolejo and prosthetist Fabian Soldevilla, Bryson gradually placed more weight on the abutment to stimulate bone growth.

By June, he was walking unassisted.

Bryson said his three daughters—ages 28, 24, and 19—were in tears when they saw him walk across the living room on his own for the first time.

A step toward the future

Beyond comfort and control, the osseointegration design may support future breakthroughs. Cheng’s research includes incorporating electrodes into the implant that could allow patients to feel touch or move robotic limbs through neural signals—advancing the frontier of prosthetic science.

Callan said interest in the procedure continues to grow, and the UT Southwestern team is evaluating additional candidates—including those with upper limb amputations—as they expand the program’s reach.

Quincy Preston contributed to this story.

Don’t miss what’s next. Subscribe to Dallas Innovates.

Track Dallas-Fort Worth’s business and innovation landscape with our curated news in your inbox Tuesday-Thursday.